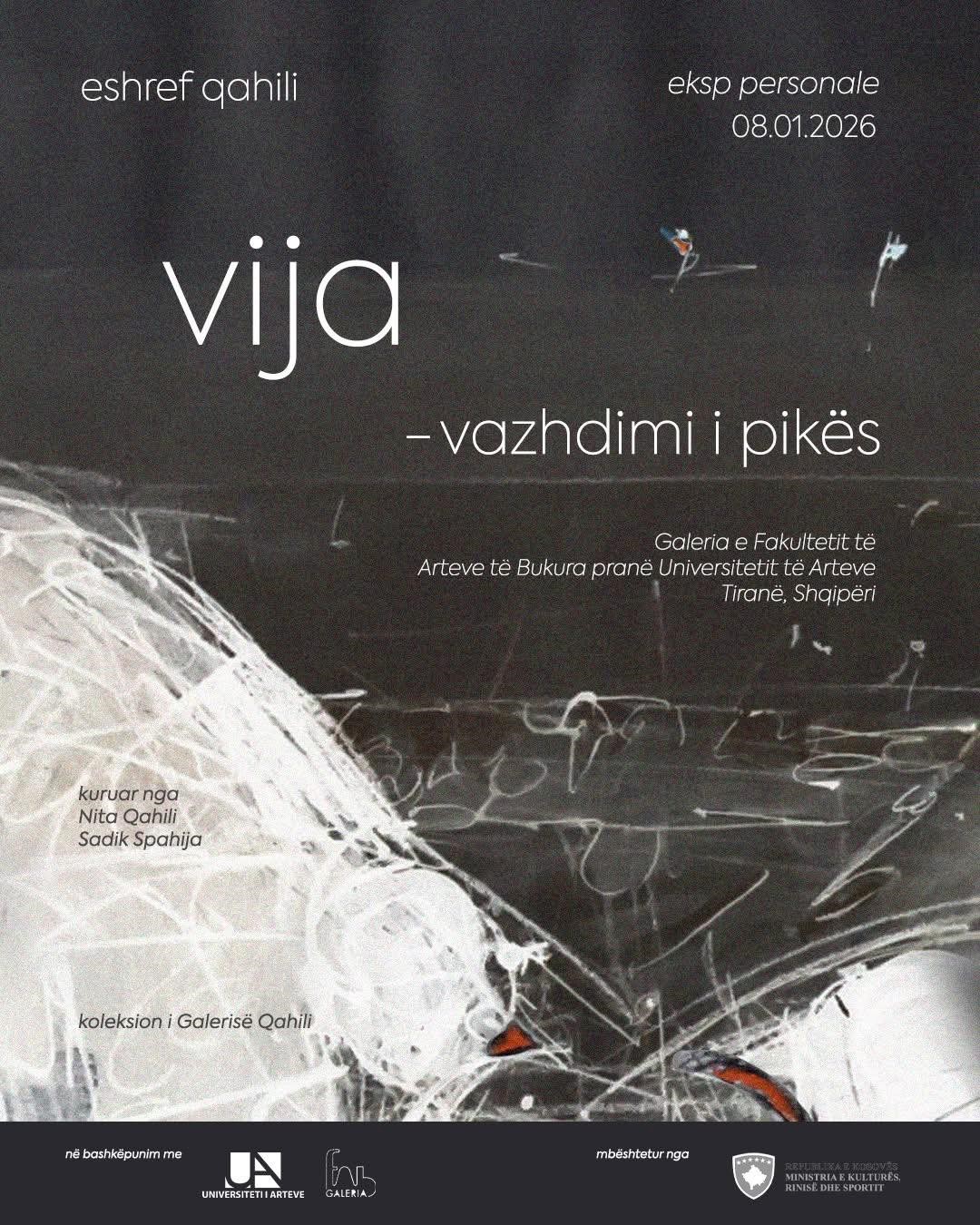

The Line, Continuation of the Point, by Eshref Qahili

The Line, Continuation of the Point

Eshref Qahili

The Line –

continuation of the point;

creation of thought;

experience of the moment;

formation of spirituality;

elevation of balance.

Eshref Qahili’s drawings present the line as the starting point of his artistic creativity. These works begin as sketches, born from moments when the artist is lost in thought, influenced by experiences and haunted by diverse temporal sensations. Through them, a connection forms between recreating and reformulating personal thoughts and experiences, indirectly interpreting approaches to cognitive behaviours. During the 16th century, drawing served as a tool for understanding and communication (Pyle, 2000). Qahili achieves this in his own drawings, using the line to study figuration, objects, or phenomena. Moreover, they explore reflections of behaviours dominant in society, often interpreted and expressed in varied, tangible ways to convey the emotions, stress, worries, and concerns of everyday life.

These are traces. Individuals. Spirits of those who have moved from one thought to another, breaking the repetitions of suffering. Dances, moments of calm and turmoil. A theatre with its everyday audience. In a single instant, monotony arises like a hailstorm that’s hard to breach and break. Yet here we often see Qahili shattering it by playing with space, filling it with colour to make you soar across loaded surfaces. But turn your gaze to drawings from other cycles, and you see the opposite: new perceptions of life in all its forms. These works create a magical life, shattering repetitions; the viewer now embodies the life fought for and attained. Like other artists, Qahili addresses concepts closely tied to his personality as an artist, where the relationship between concept and perception is essential for accessing the multidimensionality of drawing as a canon of visual languages (Rohr, 2012).

For Qahili, as for researchers in social, academic, and visual fields, drawing is a foundational pillar of artistic education and practice, vital for developing cognitive and observational skills. Drawing acts as a journey through rediscovered time, a forgotten story brought back, a period once lived. No one remembers the faces, limbs, or expressions, but we retain the memory of how we learned about that time from others and were inspired by it. The fact that these images now take on new life feels predestined, almost magical. They are like time capsules, left to be rediscovered one day. No one truly saw them then; no one understood their beauty and humanity while they were alive. And it is in these drawings that we see people as shadows, cloaked in colour yet forming powerful characters through lines drawn across the surface, via other tonal dynamics of black, or even varied textures in black and white. The chance today to learn from them, to meditate and reflect on these people and who they were, has perhaps always been part of the spiral, part of the plan.

Thus, alongside the line, the colour-filled surface plays a crucial role. Black colour blots and their repetitions, avoiding monotony, often serve as starting points for exploring ideas in other dimensions. These works break the monotony of classical drawing and challenge traditional presentation methods, creating a freer, more expressive approach, one that Petherbridge (2010) notes in contemporary artists, who reject demands for universally comprehensible visual production, attributing this scepticism to post-modern and post-structuralist relativist attitudes.

What adds uniqueness to Qahili’s works is that his drawings reflect, and one might say perceptibly convey, the influence of Daoism, blending philosophical thought with spiritual practice. Like the Daoists themselves, Qahili’s line flows and moves across diverse materials – charcoal, chemical inks, feather, or pastel – as he seeks to grasp the nature of reality and his place within it, expanding the experience of that time, the practice of awareness, and the exercise of philosophical and spiritual thought. These drawings show no effort to impose style on others; they flow naturally and reflect his people’s historical narrative. As a teacher of the era he depicts, Qahili uses the line to trace the path taken, often inexplicable and mysterious. The drawing of plots serves as a unique exercise in self-affirmation and discovery, expressing a shared sense of political engagement and resistance to the established order. As Solso (1996) puts it: “Mind and art are one. When we create or experience art, in a very real sense, we have the clearest view of the mind. We do not ‘see’ art, we see the mind.”

Drawing functions not just as a skill, but as an essential tool for thinking, communicating, and visual understanding across various visual arts media, history, and ways of life. His work displays continuity and vision, with expressions beginning in drawing and translating into other artistic media. Qahili’s drawing clarifies ideas by treating them in varied forms, serving as the precursor to every other creative and artistic endeavour. His drawing is a collage that brings life; what cannot be expressed in words appears through the line. A starting point for ideas on paper, from a single point.

University of Fine Arts, Tirana

08/01/2026 – 19/01/2026

18:00